The Battle of Corinth

Mississippi

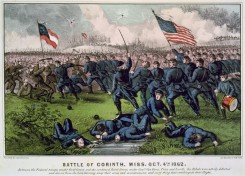

Day 2: Although the Confederates clearly have enjoyed the advantage on the first day, it does not last into the second. Maury and Green (now commanding the division of the ill Gen. Hebert) resume the assault on the Union right. Davies’ battered division takes the brunt of the assault as the brigades of Green and Gates take the lead: the principal object of the attacking Rebels is a fortified artillery position known as Battery Powell, which they capture after charging into the horrendous hail of canister, shell, and shot. The Federal brigades of Sweeny, Holmes, and DuBois begin to fade back toward the center of town, but Green does not push a pursuit. As Green is trying to recover from the murderous charge, Rosecrans rallies his retreating troops and forms a new line. After some time, Green resumes his attack on the Federal right, but by then Davies is rallied, as is Hamilton, and they throw the Rebel attack back with heavy losses. Meanwhile, Dabney Maury’s Rebel division steps off in the Confederate center, and heads for the roads that lead into the city from the West. Prominent in the Federal defenses there is Stanley’s division, strengthened by Batteries Williams and Robinett. The Southerners sweep across the open ground, Moore’s brigade of Texans, Arkansans, and Mississippians taking the lead. The Rebels move in for the final stretch but then discover that the ground immediately outside of Battery Robinett is very steep, and they lose many men in the assault.

But they finally take the earthworks, led by a gallant charge by the 2nd Texas, Col. William P. Rogers himself siezing the colors as he jumps up on the parapet, before he is killed. The Yankee counterattack retakes Robinett, so the remaining thrust of the Rebel assault sweeps around to Battery Williams, where a ghastly crossfire of Yankee rifle volleys mows them down. The rest retreat. Then, Phifer’s brigade, from Maury’s division, advances finds a gap or seam in the Union line and marches straight into town. There, they are met by Northern reserves under Sullivan, and desperate hand-to-hand fighting ensues, until the Rebels are driven out. Another attack takes the Confederates into the streets, and more street fighting drives them out again. Lovell’s division, curiously, does not advance at all. As Van Dorn orders a retreat, Lovell is given the task of rear guard. Union Victory.

|

| Texas dead at Battery Robinett, with Col. Rogers on the far left. |

Losses: U.S. 2,520 (355 killed, 1,841 wounded, 324 missing)

C.S. 4,233 (473 killed, 1,997 wounded, 1,763 captured/missing)

—The Richmond Daily Dispatch offers an editorial on the reception of the Emancipation Proclamation in Europe, particularly England, wherein they "spin" its impact to reassure their readers of English support:

—General Robert E. Lee, in response to the request of Gen. Philip Kearney’s widow, writes this letter asking the Sec. of War permission to send Kearney’s horse, saddle, and sword to her. Kearney was the Union division commander killed at the Battle of Chantilly, on Sept. 1.

Camp near Winchester, Va., October 4, 1862.

(Received October 7, 1862.)

Honorable GEORGE W. RANDOLPH,

Secretary of War, Richmond, Va.:

SIR: Mrs. Phil. Kearny has applied for the sword and horse of Major General Phil. Kearny, which was captured at the time that officer was killed, near Chantilly. The horse and saddle have been turned over to the quartermaster of the army, and the sword to the Chief of Ordnance. I would send them at once, as an evidence of the sympathy felt for her bereavement, and as a testimony of the appreciation of a gallant soldier, but I have looked upon such articles as public property, and that I had no right to dispose of them, except for the benefit of the service. In this case, however, I should like to depart from this rule, provided it is not considered improper by the Department, and I therefore refer the matter for your decision. An early reply is requested.

I am, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

R. E. LEE,

General.

—Pres. Lincoln accompanies Gen. McClellan to the South Mountain battlefield for an inspection. Then, the general and the president part ways, Lincoln traveling to nearby Frederick where a train to Washington awaits him. Called upon for a speech at the train station, Lincoln finally offers this, as reported in the New York Times:

—Sarah Morgan of Louisiana writes in her journal about the long-looked-for return of her brother Gibbes to them, after his wound in battle:

But even wounded soldiers can eat; so supper was again prepared. I am afraid it gave me too much pleasure to cut up his food. It was very agreeable to butter his cornbread, carve his mutton, and spread his preserves; but I doubt whether it could be so pleasant to a strong man, accustomed to do such small services for himself. . . . He was wounded at Sharpsburg on the 17th September, at nine in the morning. That is all the information I got concerning himself. . . . Concerning others, he was quite communicative. Father Hubert told him he had seen [brother] George in the battle, and he had come out safe. Gibbes did not even know that he was in it, until then. Our army, having accomplished its object, recrossed the Potomac, after what was decidedly a drawn battle. Both sides suffered severely.

. . . Just above, in the fleshy part, it [the bullet] tore the flesh off in a strip three inches and a half by two. Such a great raw, green, pulpy wound, bound around by a heavy red ridge of flesh! Mrs. Badger, who dressed it, turned sick; Miriam turned away groaning; servants exclaimed with horror; it was the first experience of any, except Mrs. Badger, in wounds. . . .

—Sergeant Alexander G. Downing, of the 11th Iowa Infantry Regiment, wrote in his journal of his experience on the second day of the Battle of Corinth:

No comments:

Post a Comment