June 29,

1862:

Eastern

Theater, Peninsula Campaign

Seven Days' Battles, Day 5

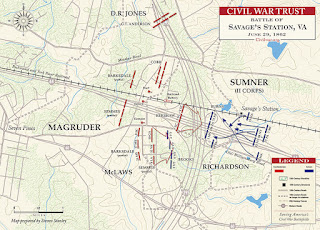

Battle of Savage’s Station: As Lee discovers the comprehensive extent and

haste of McClellan’s retreat, he devises a plan for pursuit, so as to catch

McClellan divided or at least disorganized on the tangled country roads

southeast of Richmond. He puts D.H. Hill

under Jackson’s command, and orders Jackson’s force (several divisions,

including his own, Hill’s, and Ewell’s) to move east and cross back over the

Chickahominy (hereafter referred to as “the river”), along with A.P. Hill’s

Light Division (which was really a large division), and Longstreet’s force of several divisions. Lee expects that Jackson would, being closest

to McClellan’s escape routes, be able to descend upon the Union flank or even

the rear; A.P. Hill and Longstreet, being farther away, are not expected to

catch up with the fleeing Yankees. South

of the river, Huger and Magruder are expected to strike eastward at the Yankees

also. Lee believes that McClellan will

move slowly enough that the Confederates will be able to catch up with a large

chink of the Federal army and wagon train by July 30, the next day. McClellan, however, moves faster than Lee

expects. Little Mac is convinced that

Lee and an army nearly twice his size are about to swallow up the Army of the

Potomac, and so pushes his columns southward and then departs with his

headquarters for the James River, leaving no overall commander of the corps of

Heintzelman, Sumner, and Franklin that are left as a rear guard, so that his huge

wagon train may pass through the White Oak Swamp safely to the James River

also.

|

| Maj. Gen. "Prince John" Magruder, CSA |

As Magruder advances with 14000

men, his lead column tangles with a couple of Pennsylvania regiments put there

by Gen. Edwin Sumner, commander of the Federal II Corps. Magruder calls for Huger to reinforce him,

and sits down to wait, having also heard that Jackson’s arrival will be delayed

while he re-builds a bridge across the Chickahominy that he needs to cross

on. Jackson has also received confusing

orders from Lee’s staff, and this fatally delays his cooperation with Magruder.

While Lee tries to unsnarl the problem

of Jackson’s orders, he directs Magruder to not delay and to attack the

Federals wherever he can find them. So

Magruder’s troops go forward, Kershaw’ and Semmes’ brigades pushing the

Federals. Kershaw pierces the Union

line, but for lack of support has to abandon his advantage: Union

reinforcements dislodge his troops, and the Rebel attack collapses. Magruder also orders forward a new

Confederate invention: a railroad gun---and 32-pounder Brooke naval rifled

cannon mounted behind an armored barricade and swiftly advanced on the railroad

toward the Yankee lines—the first use of a railroad-mounted battery in war. It makes little difference, however. The fighting dies out with the day’s light, with

little being accomplished except for a large bill of casualties for so limited

an action. As the Federals abandon

Savage’s Station, 2,500 Federal wounded, in addition to the wounded from this

day’s’ fight, are abandoned to imprisonment by the Rebels. Although this is a marginal tactical victory

for the North, the subsequent Union retreat make it a strategic victory for the

South. Stalemate.

|

| Battle of Savage's Station |

Losses:

Union – 1,038 Confederate

-- 473

---In

Baton Rouge, Sarah Morgan writes in her journal about the hated Federal occupation,

especially under the tyranny and military rule of the even more hated Gen.

Benjamin Butler:

Ah, truly! this is the

bitterness of slavery, to be insulted and reviled by cowards who are safe at

home and enjoy the protection of the laws, while we, captive and overpowered,

dare not raise our voices to throw back the insult, and are governed by the despotism

of one man, whose word is our law! And that man, they tell us, “is the right

man in the right place. He

will develop a Union sentiment among the people, if the thing can be done!”

Come and see if he can! Hear the curse that arises from thousands of hearts at

that man’s name, and say if he will “speedily bring us to our senses.” Will he

accomplish it by love, tenderness, mercy, compassion? He might have done it;

but did he try?

---The New

York Times, in an editorial,

considers the problem of cotton---or rather, the lack of it, if the American

cotton crop from the South is not available.

In terms of American relations with Great Britain, this is an especially

thorny problem, and partially explains the British tendency to favor the

Confederacy up until this point in the War:

. . . But when we have silenced the political jargon of

planters and demagogues in the South on this subject [slavery], we still have a

profoundly important problem that all civilized nations are interested in

solving. Where shall Cotton be had, abundantly and cheaply enough to meet the

demand formerly, but no longer, supplied by the rebel crop?

England is more interested in the answer to this question

than the United States — far more. England depends to a vastly greater extent

on the prosperity of cotton manufactories, for the preservation and welfare of

her population, than do the people of the United States. Hence it is that the

prospect of the reduction of the rebellion by our Government gives no joy and

no peace of mind in England — for it conveys no assurance of a resumption of

the enormous production of cotton in the States that once supplied the English

mills to repletion. On the contrary, England recognizes the blow that Slavery

has received, and having adopted the Southern and secession theory of “no

Slavery, no cotton,” her statesmen feel that the triumph of the Union will be a

crushing blow to England’s prosperity — plunging her manufacturers into bankruptcy, and reducing

millions to the verge of starvation.